Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview

Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview

Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview

For sports fans, one of the pleasures of March is the inevitable "madness" of the NCAA Tournament. Every year, we can expect at least a few dramatic upsets that remind us that the "little guy" truly can take down the best of opponents. In the last week, one of the teams that has captured the hearts of the sports world is Loyola University Chicago. After defeating my beloved Yellow Jackets in the first round, they pulled off the unlikely upset of top-seeded Illinois. In his book David and Goliath , author Malcolm Gladwell challenges his readers to learn why underdogs so often defeat their respective giants. Contrary to what we might assume, he estimates that 'Davids' win almost 30% of the time. In the Biblical account of David and Goliath, Gladwell argues that David, recognizing his certain doom in a traditional fight, finds an unconventional strategy to defeat Goliath. After being clothed in the traditional armor, David questioned the conventional wisdom, "I cannot go with these..." (1 Samuel 17:39). He takes off the armor and the rest is history. David refuses to fight on Goliath's terms. Gladwell says, "What the Israelites saw, from high on the ridge, was an intimidating giant. In reality, the very thing that gave the giant his size was also the source of his greatest weakness. There is an important lesson in that for battles with all kinds of giants. The powerful and the strong are not always what they seem." From a pure talent perspective, the Illinois basketball team certainly has a superior team. Like so many underdog teams before them, the Loyola Ramblers trained all year on a particular aspect where they could control their own destiny: their defense. The Ramblers big man Cameron Krutwig said, "It's been a whole season of that, man, that's our defense... We've been working our whole season for this, working our whole season on our defense." To defeat our proverbial giants, Gladwell recommends that we fight unconventionally like David. It is natural for us and our children to notice the many ways in which we can't measure up to our competitors, to other organizations, to our friends, or even our brothers or sisters. Our children might be smaller, less athletic, less intelligent, less attractive, and maybe even a combination of these factors placing them at a potential disadvantage. It is essential that we are teaching our children daily that when weighing innate skill and disciplined effort, "effort can trump ability because relentless effort is in fact something rarer than the ability to engage in some finely tuned act of motor coordination."

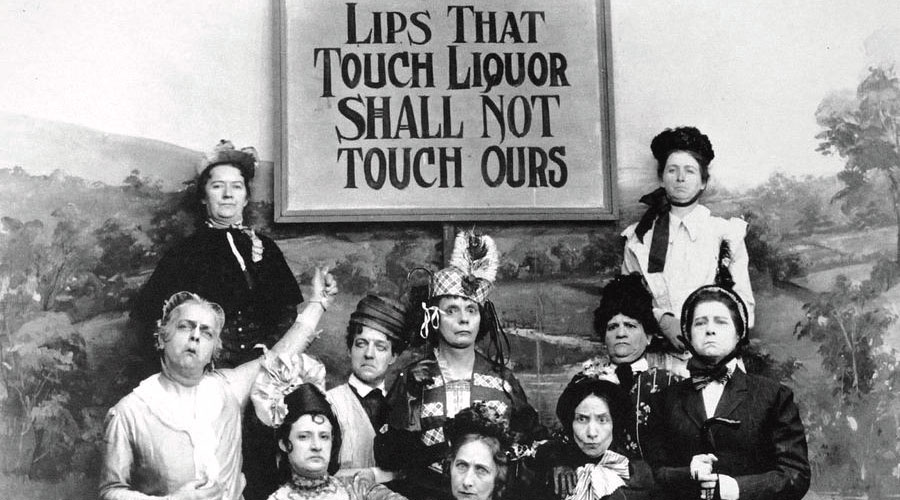

On a recent trip to Savannah, my wife and I followed our curiosity to take a tour of the American Prohibition Museum. This unveiled to us the fascinating story of the temperance movement in the 19th and 20th centuries. For most, images of the Prohibition era is what comes to mind when they hear the word temperance. I would argue that our culture is in desperate need of resurrecting the more powerful, classical meaning of this important virtue. As Inigo Montoya wisely put it, "You keep using that word, I do not think it means what you think it means." Temperance has an exalted place in moral tradition as one of the four cardinal virtues of classical philosophy and Christian theology. Essentially, temperance is defined as moderation or voluntary self-restraint. Historically, people have viewed the cardinal virtues as behaviors that can be acquired by human effort; or as Aristotle argues, "moral excellence comes about as a result of habit." Many Christian traditions have leveraged liturgical seasons as opportunities to train in themselves and in their children particular virtues like temperance and fortitude. The current religious observance of Lent helps many believers build moral fiber for self-restraint personally and also in the souls of their children. The catechism of the Catholic Church provides a more thorough and helpful definition of temperance as, “the moral virtue that moderates the attraction of pleasures and provides balance in the use of created goods. It ensures the will's mastery over instincts and keeps desires within the limits of what is honorable." Whether during Lent or at a time of your own choosing, parents ought to nurture moderation in the earthly passions of our children that often lead them to indulgence. My initial thoughts include video games, social media, phones in general, television, and sweets. The ideal place to begin this effort is by providing strong examples of voluntary self-restraint in our own lives. The self-denial of our own earthly passions will be noticed and even revered by our children. It is upon this position of credibility that we can then expect similar efforts from our sons and daughters. When done well, we are developing balanced spiritual appetites in our children and helping them establish firm control over their desires.

A particularly memorable character from the temperance movement was the radical and untamed Carrie Nation. So enraged by the debauchery that resulted from the pervasive drunkenness of her times, she would visit local taverns to distribute personally her view of divine justice. Beginning with rocks, and later with a hatchet, Nation terrorized the taverns in her community for their role in the distribution of alcohol. She desired and expected that everyone else adopt her personal conviction that alcohol was sinful in its very essence. In Mere Christianity , C.S. Lewis addresses this error saying, "One of the marks of a certain type of bad man is that he cannot give up a thing himself without wanting every one else to give it up. That is not the Christian way. An individual Christian may see fit to give up all sorts of things for special reasons-marriage, or meat, or beer, or the cinema; but the moment he starts saying the things bad in themselves, or looking down his nose at other people who do use them, he has taken the wrong turning." This "looking down the nose" is often a temptation for those that have chosen a particular temperate path and realized spiritual growth in that effort. It might be the giving up of technology, social media, alcohol, or television. Yet, temperance is also showing moderation in our application of God's word. Where it is clear, let us speak boldly. Where it is silent, may we resist the temptation to erect unbiblical fences.

Our Christian community would greatly benefit from the redemption of the classical temperance movement. Its isolated definition to the question of drink, "helps people to forget that you can be just as intemperate about lots of other things. A man who makes his golf or his motor-bicycle the centre of his life, or a woman who devotes all her thoughts to clothes or bridge or her dog, is being just as 'intemperate' as someone who gets drunk every evening." Why is self-control so important for our children? One of the Bible verses I use often in disciplinary situations comes to mind. "A man without self-control is like a city broken into and left without walls" (Proverbs 25:28). This provides a helpful and vivid picture of the dangers to our children if they don't develop a habit of self-control.

After Hurricane Michael ravaged the Gulf Coast in October of 2018, one of the more popular images from the devastation was of a shimmering white house in Mexico Beach. Owned by Russell King and Dr. Lebron Lackey, the house stood undamaged amidst a landscape of destruction. One would have thought a protective bubble had been miraculously placed over the home. The fifth chapter of Great by Choice by Jim Collins explains the idea of productive paranoia. Productive paranoia is maintaining a hypervigilance in good times as well as bad; it is to be well prepared for the inevitable chaos and uncertainty residing in our futures. Built with poured concrete, reinforced by steel cables and rebar; King and Lackey built their "Sand Palace" in good times to withstand the worst of weather conditions. The wisdom in this chapter can be applied to our work, our churches, our families, and our school. When the relational weather is good with our children, how are we as parents reinforcing our love to withstand an uncertain future? Similarly, our school must be vigilant against the dangers that can keep us from staying true to our mission; behaviors like bitterness (Hebrews 12:15), selfishness (James 3:16), and destructive heresies (2 Peter 2:1). Collins tells the story of the 1996 Mt. Everest disaster to illustrate the importance of productive paranoia. He contrasts the crucial decisions made by various climbers on the mountain days before a terrible blizzard took the lives of eight climbers. David Breashears was leading an expedition that was collecting video footage to be used for an IMAX movie. With a healthy dose of productive paranoia, Breashears decided to take his team down the mountain and wait for conditions to improve so they could safely summit at a later date. On his way down, he passed climbing guides Rob Hall and Scott Fischer who made very different decisions with the same information. Their decision to continue climbing towards the summit would cost them their lives. The thesis of Collins' argument is that, "If you come at the world with the practices of building a great enterprise and you apply them with rigor all the time-good times and bad, stable times and unstable-you'll have an enterprise that can pull ahead of others when turbulent times hit."

Imagine a world where everyone approached conversations and situations with a commitment to the question, "What can I do for you?" I think of Sam Gamgee and his longing to serve his friend Frodo in his perilous journey to Mordor. Sam says, "Come, Mr. Frodo! I can't carry it for you, but I can carry you." Sam approaches the table of human relationships with a deep-seated desire to serve and love the other with little concern for his own safety and wellbeing. Psychologist Adam Grant has researched extensively the idea of giving and taking. He argues that people can be placed into one of three categories: givers, takers, and matchers. Using a survey of more than 30,000 people, he estimates that a majority of the world (56%) falls into the matchers group. Matchers try, "to keep an even balance of give and take. Quid pro quo. I'll do something for you if you do something for me." I would argue that matching is the default position of our human nature... "you scratch my back and I'll scratch yours." Fearful of being taken advantage of by takers, we are cautious to give too much of ourselves. Yet, the example of Jesus is clearly that of a lavish giver. In Matthew 20:26-28 Jesus says, "But whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many." As we raise up our children, our goal is the giving of our lives for others that they might grow up and imitate this same spirit for others (Ephesians 5:1-2). When Frodo is facing the danger of passing through the Black Gate to enter Mordor, the question to Sam of following his friend was now easy. Tolkien says, "He had stuck to his master all the way; that was what he had chiefly come for, and he would still stick to him. His master would not go to Mordor alone." Sam's heart was consumed by one question, "Master, what can I do for you?"

One of the counterintuitive findings from Grant's research is that disagreeable people are just as likely to be givers. Grant says disagreeable people are, "gruff and tough on the surface but underneath have other people's best interests at heart." In his book David and Goliath , Malcolm Gladwell demonstrates well how disagreeable people can also be good and generous. He tells the story of doctor Emil Freireich who is recognized as a pioneer in the effective treatment of childhood leukemia. Freireich was temperamental and difficult to work with. In addition, his strong opinions often put him in opposition to the medical establishment. Yet, it was his disagreeable nature which helped him fervently pursue what he believed was a better method of treatment for leukemia. Gladwell says, "innovators need to be disagreeable. By disagreeable, I don’t mean obnoxious or unpleasant. I mean that on that fifth dimension of the Big Five personality inventory, 'agreeableness,' they tend to be on the far end of the continuum. They are people willing to take social risks—to do things that others might disapprove of." This means that we need to be careful to discourage a healthy disagreeableness that might naturally arise in our children. Similarly, we need to nurture in our Stonehaven community of learning a willingness to wrestle with ideas that our contrary to our own. For it is in this tension, that we can be better prepared to do good in this world.

If classical music was publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange, I'd venture to guess that few of us would invest in the company. Classical music appears to have a bleak future: a prime target for hedge-fund short sellers. Blockbuster, GameStop, and Classical Music Inc. all marching along on the same path towards obscurity. In his TED talk The Transformative Power of Classical Music , conductor Benjamin Zander hopes to illuminate for his audience their secret love for classical music. He says, "Everybody loves classical music--they just haven't found out about it yet." He tells the story of two shoe salesmen that travel to Africa in the late 19th century to explore the potential for selling shoes. One salesman reported back to the home office, "Situation helpless, they don't wear shoes." A second salesman had a different perspective, "Glorious opportunity! They don't have any shoes yet." Zander's optimism for the future of classical music is motivated by the idea that the natural appetite for beautiful music resides in each of us. He says, "I realized my job was to awaken possibility in other people. And of course, I wanted to know whether I was doing that. How do you find out? You look at their eyes. If their eyes are shining, you know you're doing it." The many shining eyes in the TED audience provide evidence that Zander was doing his job well. He places people into three groups regarding their proclivity to classical music: the few that adore classical music, those who don't mind classical music, and the many that never listen to classical music. In describing the latter category, he says "you might hear it like second-hand smoke at the airport." There are many in the second and third groups that are under the impression that their musical agnosticism is fully attributable to their genetic wiring... "Just the way God made me!" Zander seeks to dismantle this notion and convince us that we simply haven't been awakened to the transcendent virtues of classical music. Personally, I'm no classical music aficionado but I am fully aware that is because I haven't nourished this healthy appetite. Many might conclude that classical Christian education has a similar grim future in our current culture. I would argue that we have a "glorious opportunity" to awaken our community to the rich and vibrant nature of classical education. As we read in the fourth chapter of the gospel of John, "Look, I tell you, lift up your eyes, and see that the fields are white for harvest."

I must confess, my favorite class at Stonehaven is Kindergarten. If I'm having a particularly difficult day, the best medicine for my depressed spirit is a visit to this energetic bunch for some encouragement and laughter. This year, I have a little joke with the class where I point to one of the little girls and ask if we have a new student. I tell them the girl looks really familiar and ask her name. They all laugh and exclaim, "That's your daughter silly, it's Ruby!" I respond with bewilderment, "This isn't my daughter." Ruby throws her head back and giggles, "It's me daddy! I'm your daughter!" I am pretty sure I have repeated this farce at least ten times and the hysterical response is just the same as the first time. I can only imagine the look on the faces of our seventh graders if I tried the same buffoonery with them. Mrs. Martin recently reminded me of a quote from G.K. Chesterton where he recognizes this delightful trait in our younger children, "Because children have abounding vitality, because they are in spirit fierce and free, therefore they want things repeated and unchanged. They always say, 'Do it again'; and the grown-up person does it again until he is nearly dead." A good education appreciates the "abounding vitality" in our young children and leverages this spirit towards the acquisition of an abundance of knowledge. At the core of the grammar phase of a classical Christian education is the idea that we must "Do it again"—with song, rhyme, chant, and drama—until they have possessed Christian truth as a part of their very identity. We partner with our parents and our churches in this practice of "doing it again" so that they will never know a day that they did not know, love, and serve God. Chesterton continues, "For grown-up people are not strong enough to exult in monotony. But perhaps God is strong enough to exult in monotony. It is possible that God says every morning, 'Do it again' to the sun; and every evening, 'Do it again' to the moon. It may not be automatic necessity that makes all daisies alike; it may be that God makes every daisy separately, but has never got tired of making them. It may be that He has the eternal appetite of infancy; for we have sinned and grown old, and our Father is younger than we."

This past Saturday, a group of intrepid Stonehaven volunteers were busy tackling some various work projects around the Upper School campus. I was personally excited to test my skills as a brick mason. As I slowly labored to build a brick column, my mind wandered to a chapter from Booker T. Washington's book Up From Slavery . In the tenth chapter titled, "A Harder Task than making Bricks without Straw," Washington tells the fascinating story of how the students of Tuskegee University literally built their own school campus. In the first twenty years of the school's existence he was able to say, "In this time forty buildings, counting small and large, have been built, and all except four are almost wholly the product of student labour." The students even learned the art of brickmaking to create the very bricks of the buildings. One might wonder, how hard could it be to make bricks? Washington said, “In the early days of the school I think my most trying experience was in the matter of brickmaking... I had always supposed that brickmaking was very simple, but I soon found out by bitter experience that it required special skill and knowledge." I resonated with this sentiment after my amateurish efforts in brick masonry. This story in Washington's book illustrates the impressive perseverance and commitment he had towards the building of his school. In their first three attempts to build a kiln for bricks, they failed bitterly. "The failure of this last kiln left me without a single dollar with which to make another experiment." Many teachers advised Washington to abandon the brickmaking venture. Refusing to quit, he traveled to Montgomery to sell a watch in a pawn shop for fifteen dollars. He says, "With the help of the fifteen dollars, rallied our rather demoralized and discouraged forces and began a fourth attempt to make bricks." Finally, a kiln was successfully built and a brickmaking industry was created at the school. What Washington understood was that the work of making bricks had significant benefits beyond the obvious utilitarian value. He says, "The students themselves would be taught to see not only utility in labour, but beauty and dignity; would be taught, in fact, how to lift labour up from mere drudgery and toil, and would learn to love work for its own sake." He provides an eloquent argument for how the manual arts help to achieve goals of a true, good, and beautiful classical education. Let us continue to challenge our children to build and create things with their hands with the aim that they will find "beauty and dignity" in labor and "learn to love work for its own sake."

There are two other insights I want to highlight from Tuskegee’s commitment to erect their own buildings. First, it is not surprising to learn that the students valued their school campus in a much more meaningful way than students at other schools. He fondly recalls that, “Not a few times, when a new student has been led into the temptation of marring the looks of some building by leadpencil marks or by the cuts of a jack-knife, I have heard an old student remind him: ‘Don’t do that. That is our building. I helped put it up.” This reminds me of a similar, albeit much less significant scene from my house a few weeks ago. My youngest was none too pleased to find out that I had burned the cardboard box she had diligently been working on. What many might have seen as material primed and ready for the burn pile, my daughter saw value in her cardboard creation as it was the result of her hard work and creativity. When our children build things with their own hands, they see and treat the product with much greater respect and honor.

Finally, I was impacted by Washington's gratitude for the humble, challenging conditions the school was forced to overcome in their infancy, "As I look back now over that part of our struggle, I am glad that we had it. I am glad that we endured all those discomforts and inconveniences. I am glad that our students had to dig out the place for their kitchen and dining room. I am glad that our first boarding-place was in that dismal, ill-lighted, and damp basement. Had we started in a fine, attractive, convenient room, I fear we would have 'lost our heads' and become 'stuck up.' It means a great deal, I think to start off on a foundation which one has made for one's self." This is wisdom, to recognize that the struggle contributed to the cultivation of character and helped keep his school community from vanity.

So much to appreciate and learn from the life of Booker T. Washington. He was a man full of Christian virtue; perseverance, humility, and gratitude defined his life and legacy. Are these not the very virtues we should be seeking to nurture in our children? "Count it all joy, my brothers, when you meet trials of various kinds, for you know that the testing of your faith produces steadfastness. And let steadfastness have its full effect, that you may be perfect and complete, lacking in nothing" (James 1:2-4).

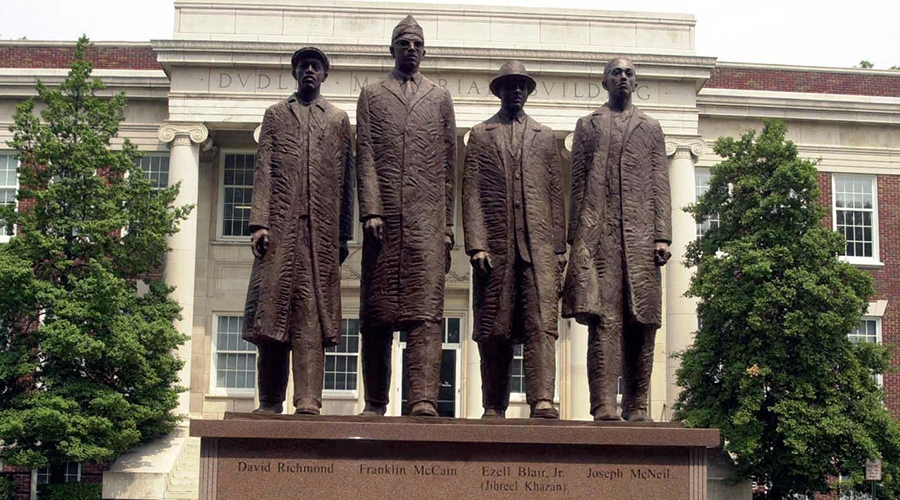

On this day in 1960, four young black students took seats at the lunch counter of the F.W. Woolworth Company store in Greensboro, North Carolina. Knowing that the store would refuse to serve black customers, the young men organized this action to protest the segregationist policies so prevalent in their community. One of the four, Joe McNeil said, “I did not believe, for one minute, that I was a second class citizen... that I was inferior in any way to whites. I couldn’t live the lie. We decided to take a stand.” The response to “The Greensboro Four” and their now famous sit-in was tremendous. The next day, fifteen more students joined the protest. The third day, 300 had joined and later 1,000 people would rally to the cause. The sit-in movement quickly spread to more than 50 cities across the South. The community targets of the protest diversified to include swimming pools, libraries, parks, beaches, museums, and transportation centers. The severe economic impact of the sit-ins and subsequent boycotts contributed to the desegregation of the lunch counter at the Greensboro Woolworth store on July 25th of the same year. Four black employees were quietly allowed to sit and be served at the store’s lunch counter. Several other businesses and public institutions would soon be desegregated under the influence of the protests. The Greensboro sit-ins were a demonstration of courage, self-control, and the power of truth. McNeil said it well, “I couldn’t live the lie.” A classical Christian education is preparing our children to live a life committed to the truth. Even when it invites ridicule and derision. No generation has lived or will ever live in a society where they are not confronted with lies and distortions of the truth. How are we preparing our children to respond to the falsehoods of their time. Dr. Martin Luther King reminds us, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy."

A powerful lesson was learned on the first day of sit-ins by Franklin McCain, one of the four original protestors. He said that an older white woman in the restaurant approached him. Understandably, he expected to be chastised by the lady. Instead, she said in a calm voice, “Boys, I am so proud of you. I only regret that you didn't do this 10 years ago.” Certainly many others were harassing the young men but this woman courageously and publicly voiced her support. McCain humbly said, “What I learned from that little incident was ... don't you ever, ever stereotype anybody in this life until you at least experience them and have the opportunity to talk to them. I'm even more cognizant of that today — situations like that — and I'm always open to people who speak differently, who look differently, and who come from different places.” We are to be training our children to be slow to judge and quick to listen. For most of humanity, a rush to judge the intent and purpose of others is our natural inclination. This weakness is present in all of us and does not discriminate by skin color. A Christ-centered classical education seeks to train a child to listen patiently, judge carefully, and extend charity at all costs.

One of the ever-present threats to the industrious of our world is that we would begin to make our work the ultimate purpose of our lives. In his excellent book Leisure: The Basis of Culture , Josef Pieper says, "Of course the world of work begins to become ─ threatens to become ─ our only world, to the exclusion of all else. The demands of the working world grow ever more total, grasping ever more completely the whole of human existence." Jesus clearly describes in Luke 19:10 the purpose of his coming to the world, "For the Son of Man came to seek and save the lost." We also see in Luke 4:18, "He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed." Jesus worked hard. To save the lost, his calendar was filled to the brim with exhausting work. Even with the infinite demands on Jesus and his disciples, he understood the importance of rest. "The apostles returned to Jesus and told him all that they had done and taught. And he said to them, 'Come away by yourselves to a desolate place and rest a while.' For many were coming and going, and they had no leisure even to eat" (Mark 6:30-31). For those feeling exhausted, you're certainly in good company. If we are serious about following Jesus, then we are to be a people devoted to cultivating healthy disciplines of rest and contemplation. In addition, we must be training these disciplines into the lives of our children. We often think of this in terms of vacations and retreats. But, we need to be training such times of rest into the daily activities of our children. Psychologist Lea Waters, argues in her article How Goofing Off Helps Kids Learn that, "There's a constructive form of goofing off that is restorative to the brain... Good goofing off happens when the person participating is competent enough at the activity that he or she does not have to focus closely on the process or the techniques. It happens when reading, cooking a familiar recipe, shooting baskets, or simply daydreaming." The value of work and rest can only be fully enjoyed when they are both integrated together and mastered in service to our Creator. Elisabeth Elliot says, "Work is a blessing. God has so arranged the world that work is necessary, and He gives us hands and strength to do it. The enjoyment of leisure would be nothing if we had only leisure. It is the joy of work well done that enables us to enjoy rest, just as it is the experiences of hunger and thirst that make food and drink such pleasures."

There is an instructive moment in Martin Luther King Jr.'s Letter from a Birmingham Jail where he makes a surprising confession, "I gradually gained a bit of satisfaction from being considered an extremist." Earlier in his letter, he had reiterated his criticism of certain extremist groups that were "perilously close to advocating violence." With his fervent promotion of nonviolent protests, if anyone could reasonably take offense to such a label, it surely was Dr. King. Yet, he reconsiders the negative connotation of the label and asks his audience to think of other historical figures that could be labeled as extremists. "Was not Jesus an extremist in love, 'Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, pray for them that despitefully use you.' Was not Amos an extremist for justice... Was not Paul an extremist... Was not Martin Luther an extremist... Was not John Bunyan an extremist... Was not Abraham Lincoln an extremist... Was not Thomas Jefferson an extremist..." The argument is clear and persuasive, being an extremist is not the issue but rather the goal and nature of your extremism, "So the question is not whether we will be extremists but what kind of extremists we will be." Seeing his extremism as a righteous pursuit, Dr. King was able to endure perceived failures and persist in his efforts towards justice and equality. As we train up our children, we should encourage and nurture a healthy form of extremism aligned with the gospel. As teachers and parents, may we be committed to equipping our children with a confidence and trust in God's word that they can persevere even when others mock their Christian convictions. Christ provides comforting words, "Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you" (Matthew 5:11-12).