Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview

Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview

Cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty grounded in the Christian worldview

My wife and I often remember the day my oldest child learned an important lesson in life. She was three years old and was preparing to join me on my bike for one of our regular rides around the neighborhood. She so enjoyed these little excursions that when I informed her that she would have to wait about 10 minutes while I got ready, she sat down on the front porch, took a deep breath, and said with a sigh, "Waiting is hard." The look on her face caused by a 10-minute delay is etched in my memory. Even with many more years of experience, I continually struggle with the challenges presented in waiting. The Christian season of Advent has historically been a time when God's people focused on waiting with anticipation for the coming of Jesus. Although I grew up in the church, I was not reared in a tradition that observed and embraced this vision for Advent. Unfortunately, I was more influenced by the pervasive materialism that often dominates the Christmas season. In his Gospel Coalition article Why Celebrate Advent? , author Timothy Paul Jones explains the challenge of celebrating Advent in our modern culture, "our calendars are dominated not by the venerable rhythms of redemption but by the swifter currents of consumerism and efficiency. The microwave saves us from waiting for soup to simmer on the stove, credit cards redeem us from waiting on a paycheck to make purchases, and this backward extension of the Christmas season liberates us from having to deal with the awkward lull of Advent." Our children learn essential virtues through waiting and can be trained well during the Advent season. In the movie The Shawshank Redemption , the unjustly imprisoned Andy Dufresne learns the power of hope in his waiting and longing for freedom. In the epic adventure story The Count of Monte Cristo , Edmond Dantes finds vengeance unsatisfying and that in the end, “all human wisdom is contained in these two words, 'Wait and Hope.'" In Mo Willems delightful children's book Waiting is Not Easy! , Gerald learns that some things are truly "worth the wait." Jones concludes in his article that, "In Advent, Christians embrace the groaning, recognizing it not as hopeless whimpering over the paucity of the present moment but as expectant yearning for the divine banquet Jesus is preparing for us." As we lean into the expectant waiting of Advent, we remind our children that Jesus will truly come again to fully restore and redeem his people unto an everlasting kingdom.

Below are some ways that parents can help nurture expectant waiting in our children during Advent:

If one were looking for a how-to video on being an anti-salesman, I'd point them to the classic comedy Tommy Boy. David Spade's character Richard Hayden delivers a motivational pep talk to Tommy Callahan (played by Chris Farley) for how to approach an upcoming sales pitch. "It's sale time, so remember: We don't take no for an answer." As he fastens his clip-on tie, Tommy seems to understand the simple message saying repeatedly and emphatically, "We don't take no for an answer." The scene cuts to a number of businessmen who say of all things, 'No.' Tommy quickly responds to each denial... "Okie dokie," "Gotcha thanks," and "Terrific, thanks for your time." With a big grin, Tommy jumps out of the chair and quickly exits the office; leaving Spade's character bemused and exasperated. Many of us cringe at the idea of working as a salesperson. Similarly, we will do just about anything to avoid the awkward interactions caused by the aggressive salesperson at your door. Although only one in nine people today work in a traditional sales position, it can be argued that we are all in the business of selling something. In Dan Pink's book To Sell is Human , he says, "But all of you are likely spending more time than you realize selling in a broader sense—pitching colleagues, persuading funders, cajoling kids. Like it or not, we're all in sales now." He goes on to argue that the very act of selling is, "part of who we are... selling is fundamentally human." One aspect of our Boosterthon fundraiser that I particularly enjoy is how it is indirectly training and teaching our children the art and science of selling. If Pink is correct, all of our children will need to learn how to do this well for their future. A central component of our Rhetoric school (10th-12th grade) is training and equipping our graduates to speak in a winsome and persuasive manner. Are these not two of the more important characteristics of an effective salesperson? A classical Christian school should be preparing our children to be the best salespeople. Ultimately, when we sell someone a true, good, and beautiful product, we are not only benefiting ourselves but also enriching the lives of others. Pink summarizes the altruistic goal of a good salesperson, "To sell well is to convince someone else to part with resources—not to deprive that person, but to leave him better off in the end."

My son recently became interested in throwing and catching footballs in our home. The recent popularity of football on the Stonehaven playground is certainly the genesis of his new interest. To the chagrin of my wife, I believe this has resulted in a broken bowl and the spilling of at least two drinks. I digress, this is mostly beside the desired point. As he gained more confidence in the stationary version of the exercise, he asked me to throw the ball in front of him, forcing him to make a diving catch into the living room couch… “Come on dad, this is too easy.” He was ready and eager to conquer a new challenge. And yet, the increased complexity inevitably resulted in increased failure (dropped footballs). An interesting question at this moment is the following, what is the optimal rate of failure? It certainly isn’t best if the exercise is so easy that he catches every ball. Nor is it productive if I were to imitate Tom Brady and he dropped every pass and suffered several chest contusions as well. Researchers have found that learning is optimized when the rate of failure is about 15%. In other words, we learn best when we get things right 85% of the time. We see that when our children are challenged just beyond their current ability, they are placed in the best environment to learn new things. Researchers have found this rule to apply to learning new languages, learning a musical instrument, catching footballs, and in classroom lessons. This consistent exposure to failure also instills a deep understanding in our children that failure is necessary for their growth. This idea aligns well with one of the essential laws of teaching we follow as a classical Christian school. In John Milton Gregory’s book The Seven Laws of Teaching , he argues, “To teach again what is already known and understood is to mock the pupil’s desire for knowledge, and to deaden his power of attention by compelling him to walk the weary round of a treadmill, in place of leading him forward to the inspiration of new scenes and the conquest of new truths. No more fatal blow can be dealt to a child’s native love of learning than to confine its studies too long to familiar ground under the fallacious plea of thoroughness.”

During a recent trip to the beach, I was once again impressed by the never-ending nature of human ingenuity. Friends of ours introduced us to the Shibumi beach shade: a lightweight canopy connected to a single arch powered by the ever-present ocean breeze. A walk down the beach revealed that we weren’t the only group to have discovered the simple, yet brilliant Shibumi craze. Is it possible that I would never again have to run wildly down the beach to clumsily retrieve a runaway beach umbrella? And people everywhere wondered, “Why didn’t I think of this!” The Shibumi inventors say they were just trying to create a product for personal use that could replace the, “flimsy beach umbrellas and bulky tents that never provided quite enough shade, were too heavy to carry, too complicated to assemble, and might be carried down the beach in a strong gust of wind.” It is evident that their brilliant creation originated from discontentment: a healthy form of discontentment. Frustrated from their past experience with the imperfect solutions on the market, they refused to accept that all possible solutions for sun shade had been exhausted. Psychologists like Malcolm Gladwell and Jordan Peterson call this a productive form of disagreeableness. As Christian parents, we are often encouraging and celebrating agreeable and grateful behavior in our children. If one of our children complained about the problems of a beach tent we might ask them to be grateful for what they do have… or even use the Stonehaven shout out, “Enough… is as good as a feast!” Gladwell asks the right question, “Is it possible we are raising a generation of people who are less disagreeable than previous generations? That the effect of all the things we’ve done in good faith to make young people much more aware of and solicitous of each other’s feelings has had the paradoxical effect of making it harder for them to try something truly crazy and weird and innovative?” How can classical Christian schools nurture a healthy discontentment and a boldness to disagree with the status quo that can help our children find creative solutions to the problems of our world?

The philosophy of a classical Christian school seeks to cultivate a rich conversation willing to debate the merits and faults of all ideas. In Dorothy Sayers’ influential essay The Lost Tools of Learning , she uses the example of a group of boys arguing for days about a local weather occurrence to promote the value of rational argumentation and debate… “a number of small boys enjoyed themselves for days arguing about an extraordinary shower of rain which had fallen in their town—a shower so localised that it left one half of the main street wet and the other dry. Could one, they argued, properly say that it had rained that day on or over the town or only in the town?” In this portion of her essay, she goes on to encourage educators to present issues and ideas in the classroom that will generate diverse opinions… stoke the flames of debate so that you can show them how to do it well. Sayers anticipates objections to her ideas, “It will doubtless be objected that to encourage young persons at the Pert Age to browbeat, correct, and argue with their elders will render them perfectly intolerable. My answer is that children of that age are intolerable anyhow; and that their natural argumentativeness may just as well be canalised to good purpose as allowed to run away into the sands.” It is natural for our children to become disagreeable during this phase of their life. Therefore, our goal is to help them do it rationally, persuasively, and with grace. Are you not content with this beach tent? Instead of complaining, let’s get busy thinking of a better idea. Do you disagree with this school policy? Consider why it exists and propose a policy that better achieves the goal. Mr. Proffitt recently had his students make an argument for one date to add to the history timeline in the place of one of the current dates. Along with their recommendation they were to provide an argument for why their selection was superior to the existing date. This is how we can generate healthy disagreeableness in our children.

Our primary goal as Christian educators and parents is that our children treasure truth, do good, and love beauty. It is not that they never disagree with us and imitate us in every way. If they don’t like a particular activity, we could ask, “How do you think we could have done it better?” If they don’t like the ending to a movie or book we would ask, “What would have been a better ending to this story?” It is not enough to be disagreeable. Ultimately their discontent needs to be used as fuel for finding better solutions to the many problems in our world. And in so doing, their disagreeableness becomes an unexpected virtue.

When my children were one and two years old, I would often throw balls towards their hands. I’d watch my grinning son or daughter stiffly hold out their hands and essentially make no effort to catch the coming ball. At best, I’d see their eyes slightly move. It would hit their chest, arms, or legs and fall to the floor. Occasionally, a well-thrown ball would settle in their arms and those watching would gleefully celebrate their amazing ability to do nothing and yet still catch the ball. After several sessions of the same ritual, I’d see my children beginning to mentally and physically grasp how this hand-eye coordination exercise is supposed to work. I throw the ball, you follow with your eyes, and move your hands in a manner so as to catch the ball. There were hundreds of balls dropped by my children. No rational parent would quit throwing balls with their child because their little girl didn’t catch a single one in their first practice session. There are many effective tools of learning that are often abandoned by parents and educators when they don’t achieve the desired results in the early going. One valuable tool for learning that requires patience and perseverance is that of Narration: the art of telling back in your own words what you have heard or read. Similar to throwing a ball towards a one-year old, parents and teachers should have low expectations of the short-term results when practicing narration. Miss B. Millar, an educator from the early 20th century and proponent of Narration, says, “To tell again what they have read, sounds very simple, but in reality it involves hard work. It is impossible to tell what they do not know, and to make an orderly narration of any passage read, involves repeated putting of the question ‘what next?’ by the mind to itself, till the whole thing stands out clearly in the memory.” Think of the lost look on your child’s face when you ask them, “Tell me what you heard in the sermon from Pastor Ames.” Narration is hard work. It requires sustained attention in a world full of distractions. Imagine though making it a known practice that every Sunday afternoon you were going to ask this question of your Fifth Grade son. Not only were you going to ask the question but you were expecting him to provide an acceptable summary of the major ideas from the sermon. Your son would be sitting in the church service knowing that his attention was expected. If parents were consistent in this practice, undoubtedly their son would mature over time in his ability to attend to a lesson. As we encounter the academic struggles in our children, let us never grow weary of throwing the ball over and over again. Trust me, they will learn to catch it if you stick to it.

Here are some ways in which are parents can partner with our school and implement Narration in the home:

Riveting, dramatic, and thrilling are some good words describing the last two playoff games for the Atlanta Braves. In game two last night, the Braves provided some more late-night magic to take an unexpected two-game lead over Mr. Mastrianna's heavily-favored Dodgers. I do remember last year Mr. M! It was a similar scene on Friday night when Stonehaven dads Flavio Garcia and Robin Rammessar used some razzle dazzle on the basketball court to finish off their opponents concluding our first-ever monthly dads basketball gathering. The place of athletics in modern schools can trace its roots to the beginning of the 19th century. A schoolmaster in Berlin, F.L. Jahn, introduced gymnastics in an effort to train healthy recruits for the anticipated struggle with Napoleon. In essence, athletics in the modern school era was originally designed to create a virtuous warrior. What is the role of athletics in a classical Christian school today? Although the primary aim is no longer to prepare men for war, the athletic field is still a battleground for the cultivation of virtue. As Stonehaven continues to grow through the 12th grade, we are excited and committed to building an athletics program that serves and strengthens our mission to cultivate truth, goodness, and beauty in our children. Sports provide a proverbial playground for us to practice, train, and instill Christian virtue in our children. The Ambrose School, a classical Christian school located in Idaho, says in their philosophy of athletics that, "Within a classical school, athletics provide an opportunity for him to exercise his morality in a competitive world: there, the competitor is to do his best to achieve victory by exercising rightly-ordered virtue... If virtues are wrongly ordered (e.g. if sportsmanship is made subordinate to ambition), the result might be a statistical win, but an 'ugly' victory." Sports provide an outlet that can both place an encouraging spotlight on the virtue dwelling within our children but can also expose their hidden vices that might otherwise go unnoticed. We should welcome this exposure as a low-stakes moment where we can redirect our children away from a natural inclination towards vice. Our role as parents and coaches is especially important when we detect a disordered desire to win at all costs, a struggle to cooperate well with teammates, or a tendency to quit when the going gets tough. A healthy athletics program encourages self-discipline, fortitude, teamwork, and integrity and therefore will contribute to the Christian culture of the school. Most importantly, we want to help our children see and understand how they can bring God pleasure through their athletic endeavors. In the classic movie Chariots of Fire, runner Eric Liddell articulates well the comfort of a Christ-centered view of sports, "He also made me fast and when I run... I feel his pleasure."

Facebook's mission is, "to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together." Raise your hand if you think Facebook is bringing the world closer together. Although Facebook has many virtues, I doubt that such a technology possesses the power to unite our fractured world. Centuries ago, the idea of community in a person's village took on a vastly different meaning than the "virtual villages" promoted by Facebook and Instagram. The Facebook vision of community is defined primarily by the practice of communication. As if the quantity of words, pictures, and likes embodies a community. If communication is the most important measure, then Facebook is certainly one of the primary creators. However, author Wendell Berry provides a more traditional definition saying, "Community is not made just by communication. It is a practical circumstance. It is composed of people who have a place in common. But it is made by people's willingness to be neighbors, good and faithful servants, to one another. It survives by its members' recognition of their need for one another, if only to keep the small children from getting lost or run over, or to keep their trash out of the streams and roads." Community is built and sustained through meaningful relationships. Stonehaven provides a daily opportunity for our children, parents, and teachers to have "a place in common" and embrace our "need for one another." Writer Gracy Olmstead provides a helpful distinction between these two very different villages saying, "while real villages/towns are often nosy and gossipy and contentious, the people within them live, work, worship, and rest together. Their lives are inexplicably intertwined, and cannot be turned off or logged off. Thus, people in a real village must learn to forgive, to work through differences, to heal hurts and find societal solutions to real-world dilemmas. The 'virtual village,' on the other hand, gives us the opportunity to disconnect whenever we become offended or angry. It enables us to be as nasty, narcissistic, and demeaning as we please—with very few real-world consequences. And this creates a dangerous sort of atmosphere, one that is in fact poisonous to real community." Although we live in a big city, our school provides a precious common place to live, work, worship, and rest together. Let us show our children what real community looks like and maybe then we can truly bring the world closer together.

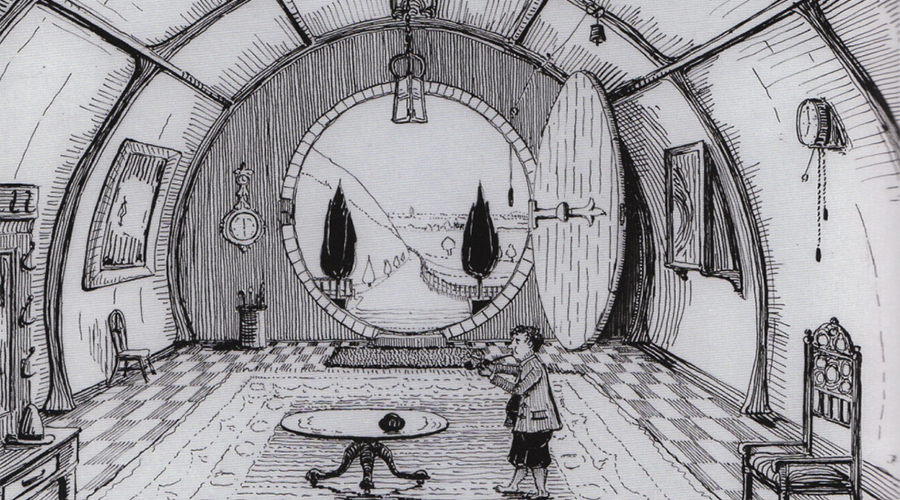

Tolkien's classic adventure tale The Hobbit begins by saying, "In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort." What a wonderful opening to a truly amazing adventure story. Any honest reader is instantly challenged to imagine the nature of this unknown world. What is a hobbit? What do they look like? What is a hobbit hole and what makes it comfortable? Why do they live in holes in the ground? Fairy tales possess a unique and remarkable ability to pull our imagination away from the world we think we know so well. One of the threats to our growing up is the temptation to believe we have acquired a full understanding of God and his creation: We are too old for fairy tales. In an educational environment that is constantly demanding that every aspect of learning be useful for a child's vocational future, fairy tales will struggle to find the light of a day in a modern classroom. Atheist Richard Dawkins provides the rationalist argument against such stories, "I think it's rather pernicious to inculcate into a child a view of the world which includes supernaturalism – we get enough of that anyway. Even fairy tales, the ones we all love, with wizards or princesses turning into frogs or whatever it was. There's a very interesting reason why a prince could not turn into a frog – it's statistically too improbable." It's also statistically improbable for a child to be born of a virgin or for a man to rise from the dead on the third day. In essence, Dawkins is arguing that children are too old for fairy tales as well. In his famous essay, On Fairy Stories , Tolkien says, "We need, in any case, to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity." Tolkien, Lewis, and the great storytellers throughout history believed that good fairy tales summon us to a better understanding and appreciation of our own world. As our imaginations explore the wonders, curiosities, and magic of another world, we can't help but see our own world with greater clarity. Louis Markos, the author of the book On The Shoulders of Hobbits , says fairy tales evoke, "awe and wonder: not only toward the Secondary World but toward the Primary World as well. For fairy stories have the power to cleanse our perception and, by so doing, enable us to see our own world afresh, as if for the first time." One way our parents can be partnering with us is by regularly reading fairy tales with their children in the home. As Lewis writes in the preface to The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, maybe we are, "old enough to start reading fairy tales again."

"Anyone? Anyone?" says actor Ben Stein in a classic scene from the movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off . In a hilarious monotone voice, Stein portrays an epically dull economics teacher seeking to explain the fascinating history of the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act, "In 1930, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, in an effort to alleviate the effects of the... Anyone? Anyone?... the Great Depression, passed the... Anyone? Anyone? The tariff bill? The Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act? Which, anyone? Raised or lowered?... raised tariffs, in an effort to collect more revenue for the federal government." In an impressive display of cinematography, the camera captures a collection of close-up shots of student responses. From expressions of intense boredom to a comatose student drooling on his desk, the teacher is obviously struggling to attract interest in his lesson. In our effort to return to a historic and traditional form of learning, the last image that should come into our mind of "classical" education is the monotonous drone of spiritless lecturing. Classical education is not as some might imagine, a return to straight rows, restrictions on laughing, and boring lectures about the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act. A robust, classical Christian education integrates a rigorous curriculum with a culture of joy. A culture of song, laughter, and wonder should fill the classrooms of a classical Christian school. One place where we are strategically investing in our culture of joy is a daily focus on singing together during Morning Meeting. Martin Luther claimed that, "Beautiful music is the art of the prophets that can calm the agitations of the soul; it is one of the most magnificent and delightful presents God has given us." In the first five weeks, we have already been impressed with both the musical growth in our students but also the positive impact singing can have on our school culture. We trust that we are only reaping the initial benefits of this investment and believe that we will reap even greater rewards as we lean into our commitment to become a Schola Cantorum (Singing School). In Tolkien's book The Hobbit , the Dwarf-King Thorin Oakenshield said it well, "If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world."

Mrs. Johnson has been teaching our Lower School a delightful children’s song originally from Morocco called A Ram Sam Sam . Click the link below to hear this song.

One of the more destructive errors of modern philosophy is that the chief aim of our lives is an emotional state of happiness. New age philosopher Deepak Chopra proposes that, "the goal of all goals is happiness and our emotions are like road signs on that journey toward the goal of happiness." When such a view of our ultimate purpose is adopted by our children, we are equipping them with unrealistic expectations for their future. How will our children respond when their lives don’t align with this penultimate goal? Inevitably, our children will encounter challenging relationships, vocational frustrations, and even a number of hard seasons of suffering. Psychologist Jordan Peterson criticizes the happiness goal saying, "Happiness' is a pointless goal... what happens when you’re unhappy? Happiness is a great side effect. When it comes, accept it gratefully. But it’s fleeting and unpredictable. It's not something to aim at – because it's not an aim. And if happiness is the purpose of life, what happens when you're unhappy? Then you're a failure. And perhaps a suicidal failure. Happiness is like cotton candy. It's just not going to do the job." The word sin in the Bible comes from the Greek word Hamartia which means "to miss the mark." In our Christian worldview, we have sinned when our actions and words miss the target of God's will. The Bible does not place happiness as man's chief end. Happiness is good, a thing to be cherished when God provides it in our lives, but it will serve our children poorly as a telos for their existence. Christian parents and teachers would be wise to avoid telling their children that the cotton candy of happiness will satiate their spiritual hunger. I can think of two better answers that will give our children a better target for their lives. First, "to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God" (Micah 6:8). A second is from the first question in the Westminster Shorter Catechism, "Man's chief end is to glorify God and enjoy him forever.” As parents and teachers, let's make sure we are pointing our children towards the right target.